Supply, Supply, Supply

Supply. The short-term markets will be inundated with Treasury bills in coming months as the Treasury refills its cash account, manages seasonal revenue flows and…oh yes, funds the deficit.

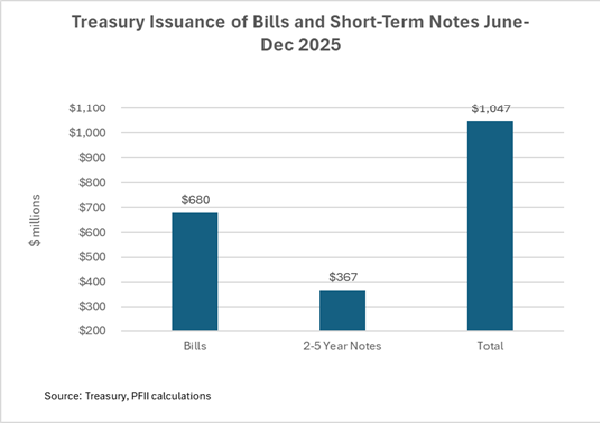

• The Treasury’s quarterly refunding announcement this week laid out a plan to increase issuance of Treasury bills and short-term notes—those maturing within five years—by nearly $1.1 trillion(!) between June 30 and year-end. Even in the outsized world of debt, deficits, and bond markets that’s a big number.

• If you are a buyer—state and local governments and LGIPs are large buyers of Treasuries—this should be a good thing for yields as more supply should support or push them higher. If you are a seller the cost will be borne ultimately by the taxpayers, but that’s another story.

• This surge will affect the overall market as other issuers and dealers make room for the big one. There are many factors that determine the level of rates, market liquidity and relative value but Treasury’s issuance plans are a significant one. They should put modest upward pressure on short-term Treasury rates and increase the supply of these risk-free highly liquid assets. The added demand will have to come from somewhere (bank deposits perhaps?) and issuers of commercial paper and corporate bonds will likely have to increase their offering rates to keep pace.

The details

Treasury is a regular issuer of debt with bill auctions twice a week, short-term note auctions monthly and sales of long-term securities on a quarterly basis. Once a quarter Treasury publishes a plan that looks forward for three to six months so the markets can gauge the impacts of its largest issuer. The current refunding announcement, released earlier this week, sets the stage for issuance through the end of the year and provides some basis for guessing plans for the first quarter of 2026. In the public funds space that’s something like the half life of a portfolio so we should pay close attention.

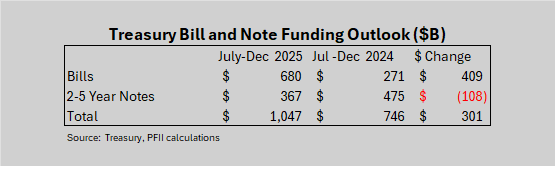

Treasury’s announcement has a couple of notable elements. The accompanying table summarizes its plans for issuance of bills and short-term notes. In the second half of the year the government plans to increase the amount of bills outstanding by nearly $700 billion, and short-term notes by $367 billion. The total is up by $301 billion from the same six-month period last year.

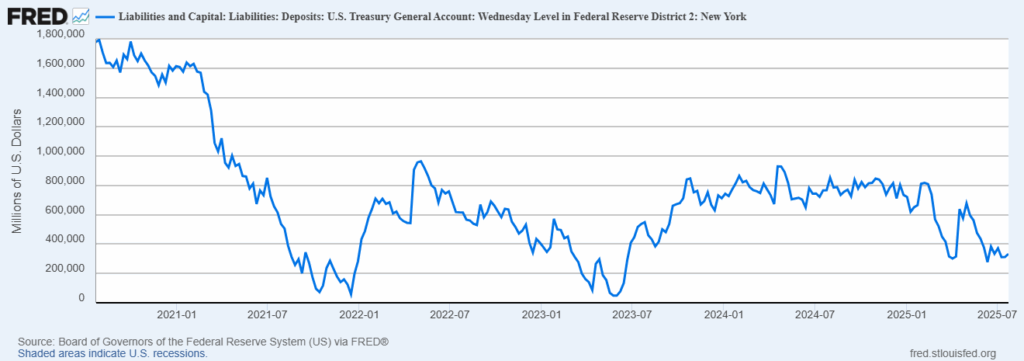

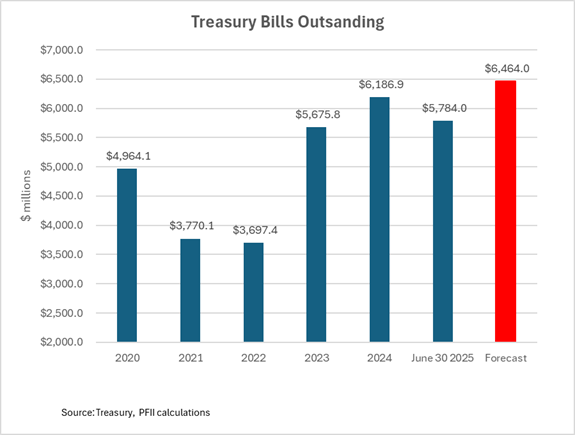

Treasury is planning to increase its reliance on bills which mature within 12 months. Some of this tilt toward bills is because the debt ceiling kept the Treasury from expanding issuance in the first half of the year, even though the growing budget deficit required more spending. Treasury targets a cash balance of about $850 billion of working capital. It drew this down to under $300 billion between January and June and, with expansion of the debt ceiling by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, it is now rebuilding this balance.

In recent history the Treasury has used the short-term bill market to fund about 20% of its issuance, maintaining a weighted average maturity of its debt in the 60–70-month range.

Quick math: if total Treasury debt is ~$36 trillion, Treasury will target about $7 trillion in bills. And if the budget deficit expands by $2 trillion a year, Treasury will grow the bill supply by $400-$500 billion in future years.

Treasury bills outstanding totaled about $5.7 trillion as of June 30. The level is below the year-end 2024 amount, largely due to distortions from the effects of the debt ceiling, but in line with growth in 2023 and 2024. Still, for the market to absorb this issuance will take some doing.

More quick math supports the conclusion that Treasury’s dominance of the money markets will continue to grow as long as the budget deficit expands on its current path. The Trump administration hopes to reduce growth in the deficit through a combination of tariff revenue and aspirational economic growth, though many private economists and the Congressional Budget Office are skeptical. To wit: Treasury is using a forecast of borrowing needs to decline to $1.6 trillion by 2027, but the CBO and primary dealers forecast a continuation of current levels–$2 1 to $2.3 trillion.

That could mean growing bill issuance by $400-$500 billion year, and growing issuance of two-to-five-year Treasuries by $600 billion or more a year. These are big numbers, and mean Treasuries will expand their dominance of the investment grade markets. For perspective, the total volume of commercial paper outstanding is about $1.3 trillion. Total outstanding Federal agency obligations are about $2.0 trillion and annual issuance is less than $400 billion a year. So, we should expect Treasury holdings in investment grade portfolios to expand.

Treasury’s announcement also highlights another key aspect of its financing plans: they are highly dependent on this short-term market. While much is made of the quarterly auction results for 10-and 30-year Treasuries, and Treasury issued $444 billion of these in the first half of the year, that amounted to less than ten percent of the overall issuance of Treasury debt.

Treasury has expressed no interest in terming out its debt at current interest rates, choosing instead to pay current rates with roll-over risk on the belief that rates will be lower in the long term. But whether its rate outlook is reasonable, Treasury has little choice, as it’s hard to see a path for the long-term market to absorb the level of supply to make a real impact on the overall debt profile.

Who Will Buy This Debt?

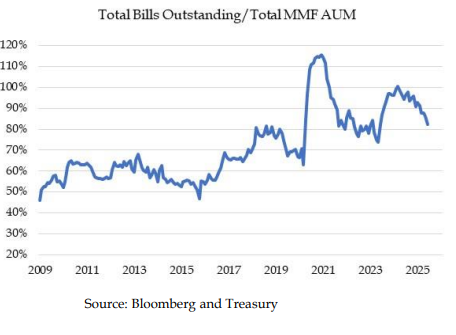

Demand could come from a number of sources. Money funds, with assets of about $7.7 trillion, are the largest current buyers of bills. They held about $2.6 trillion of Treasury debt as of June 30, largely bills. Money fund assets have expanded rapidly in recent years, and growth has kept pace with growth in the supply of short-term Treasuries.

The source of this growth is a bit of a mystery. Perhaps it represents an element of wealth generated by a strong stock market. Treasury’s announcement included the following chart that suggests that money market funds could step up, but without growth in their assets this would mean reducing holdings of other assets, most likely repurchase agreements.

Public agencies hold about $1.6 trillion of Treasury debt, much of it in Bills. This amount has grown in recent years as public unit investment assets have expanded. With reported stresses in state and local government budgets it doesn’t seem like the recent trend of strong growth will continue. It could well be that public units continue to shift investment assets in favor of Treasuries but that would be at the expense of other sectors. It all depends on relative rates.

Investors could also draw down bank deposits. But this would not please the banks, and it might crimp lending capacity, something the Trump administration would not favor.

Finally, the crypto barkers say the growth they expect in stablecoins will create new demand for the bills. But as I’ve observed, unless you are a central bank you can’t create money so assets that flow into stable coins would have to come from somewhere. Money funds? Bank deposits? Cash? So perhaps this is a bit of wishful thinking.

How about the Federal Reserve? Not likely unless the Fed were to come under control of Trump, and even then, printing money to intermediate debt is likely to be a bridge too far.

Bottom Line

There should be no doubt that Treasury will be successful in borrowing this amount, though it is likely the volume will push rates higher. The flood of new bills could widen bid/offered spreads on pre-existing (i.e., “off the run”) bills. And other money market issuers will have to step up to maintain market access. That’s hardly the end of the world, but it does mean buyers will command an added premium for investing in Treasuries.

This may seem like an odd statement to make. After all, if Treasuries are risk-free and highly liquid how could/would we measure this? One way is by comparing Treasury yields on rates for one-day interest rate swaps contracted for a term equal to that on the Treasury. The math is a bit complicated but by this measurement two-year Treasuries went from paying a yield about equal to the swap rate several years ago to paying about 25 basis points more. Treasury’s access to the markets will remain unchallenged, but the cost of such access appears to have risen, and current plans suggest this upward pressure will continue.