What to Do When the Fed Moves

The Federal Reserve is on the cusp of lowering short-term interest rates. Softening labor markets, inflation that has not (yet?) reacted to the new tariff regime and unrelenting political pressure from the Trump Administration are likely to lead the central bank to resume its easing later this month. (No, the Fed is not immune to political pressure, though the “independence” advocates would like us to believe it is.)

The Federal Reserve is on the cusp of lowering short-term interest rates. Softening labor markets, inflation that has not (yet?) reacted to the new tariff regime and unrelenting political pressure from the Trump Administration are likely to lead the central bank to resume its easing later this month. (No, the Fed is not immune to political pressure, though the “independence” advocates would like us to believe it is.)

What should public funds managers do in response? We ran a number of simulations on an investment model to shed light on this question. The simulations focused on income earned over a three-year period for an investment in an LGIP, an investment in a one-year Treasury bill and an investment in a three-year Treasury note. Some of the description below is a bit wonky, but I’ve tried to keep it simple. For those who would like added details feel free to reach out to me by email or using the Comments section on the website.

First a couple of big picture points:

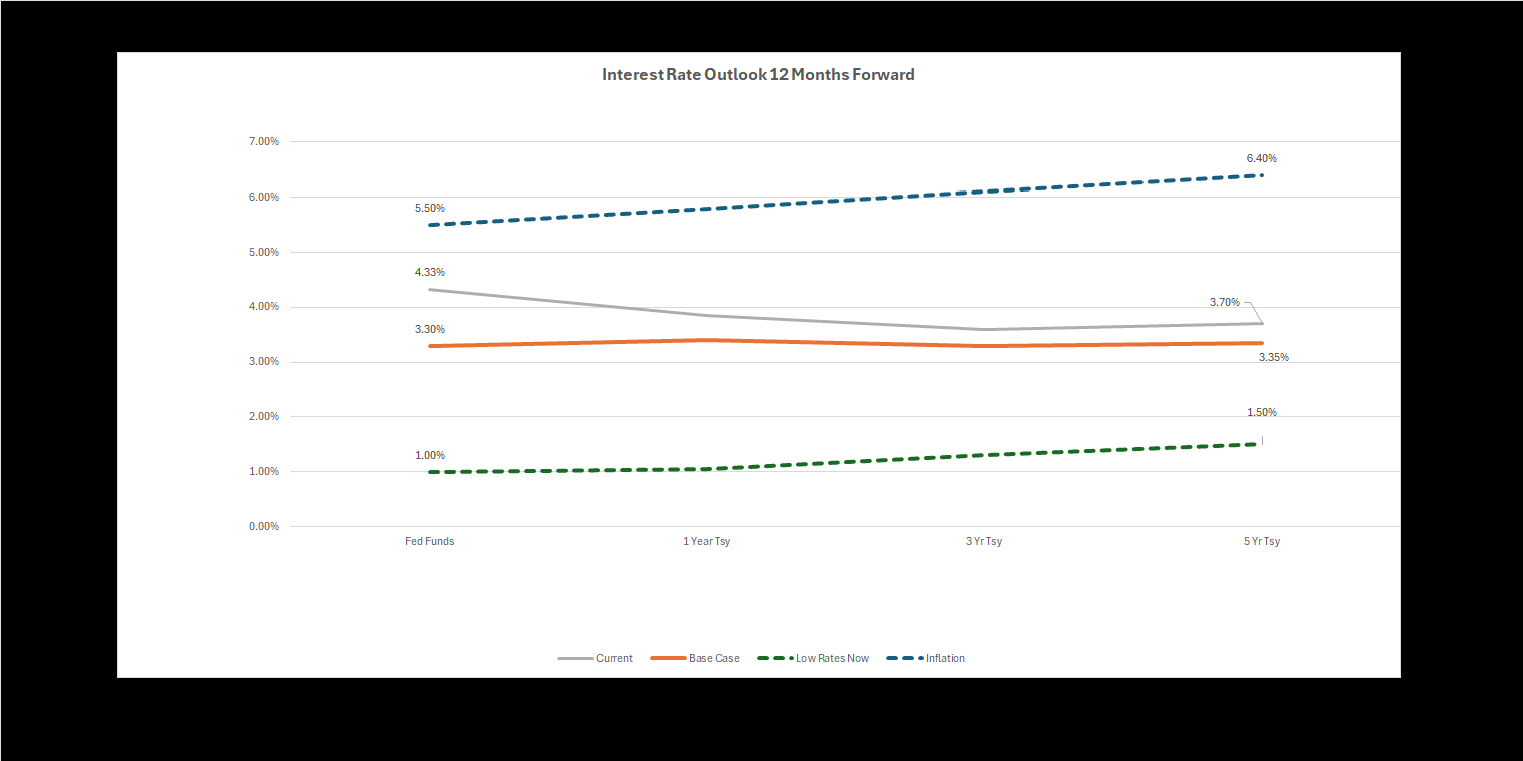

- The simulations focus on investment maturity and look at results under a variety of scenarios: A base case assumes the Fed cuts rates along a path laid out in its quarterly Summary of Economic Projections and consistent with current investor market expectations. This means gradually reducing the overnight rate to three percent over the next 12 months. Other short term rates would respond to this and fall as well.

- We also look at two other paths: a Low Rates Now path that relates to Trump’s call for the Fed to ease rates to one percent, and an Inflation path that seeks to track the market if tariffs boost inflation in coming months, causing the Fed to reverse course and tighten. Outcomes like these are in the tails of interest rate forecasts, but tail risks are more likely now than in normal times. No matter how strongly you believe in a particular market forecast it’s prudent (essential!) to stress an investment strategy under alternative scenarios to see what the result would be.

- The simulations are limited to LGIPs and Treasury securities because these provide safety and liquidity, though liquidity for the longer-duration investment comes at a cost. One way to think about this is that a portfolio with a duration of 2.5 (which is close to the duration on the current three-year Treasury note) will change in value by something equivalent to two-thirds of the income earned in a year A year later the duration of this investment will have drifted to a duration of 1.5 and the cost would be about one-third of income. So, liquidity at a price if yields rise (or a profit if they fall). In the Base Case selling the three year Treasury Note prior to maturity should result in a gain.

- The assumed LGP investment includes credit instruments (we use a forecast for prime LGP yields in the simulation) but there is no credit in the one and three-year investment portfolios. Back of the envelope, a government-only LGIP is likely to produce income that is 10-15 basis points lower than our LGIP model. An allocation of the one- and three-year portfolios to a moderate amount of investment-grade credit (say one third of the portfolio) is likely to boost income by 10 to 20 basis points. This is not so significant as to change the big picture of the scenario analysis.

- Our analysis is focused on income and simple interest over the investment terms because this is what impacts state and local government budgets. That’s not to discount the importance of total return analysis in portfolio management, but unrealized gains and losses go to a different place in financial statements and don’t help pay for teachers and public safety.

The Results

To keep this simple, let’s address the question of whether to keep investment assets short and liquid—in an LGIP—or to invest it out for a term, here 12 months and three years. We assume the investments are of surplus assets, so the income is drawn every 12 months, but the principal is not. (Investing to meet cash flow draws can employ a similar analysis.) And we assume that an initial investment for less than three years is reinvested monthly for the LGIP and annually for the 12-month Treasury bill, at the current rates.

A summary of the interest rates used in the analysis is shown in the chart below:

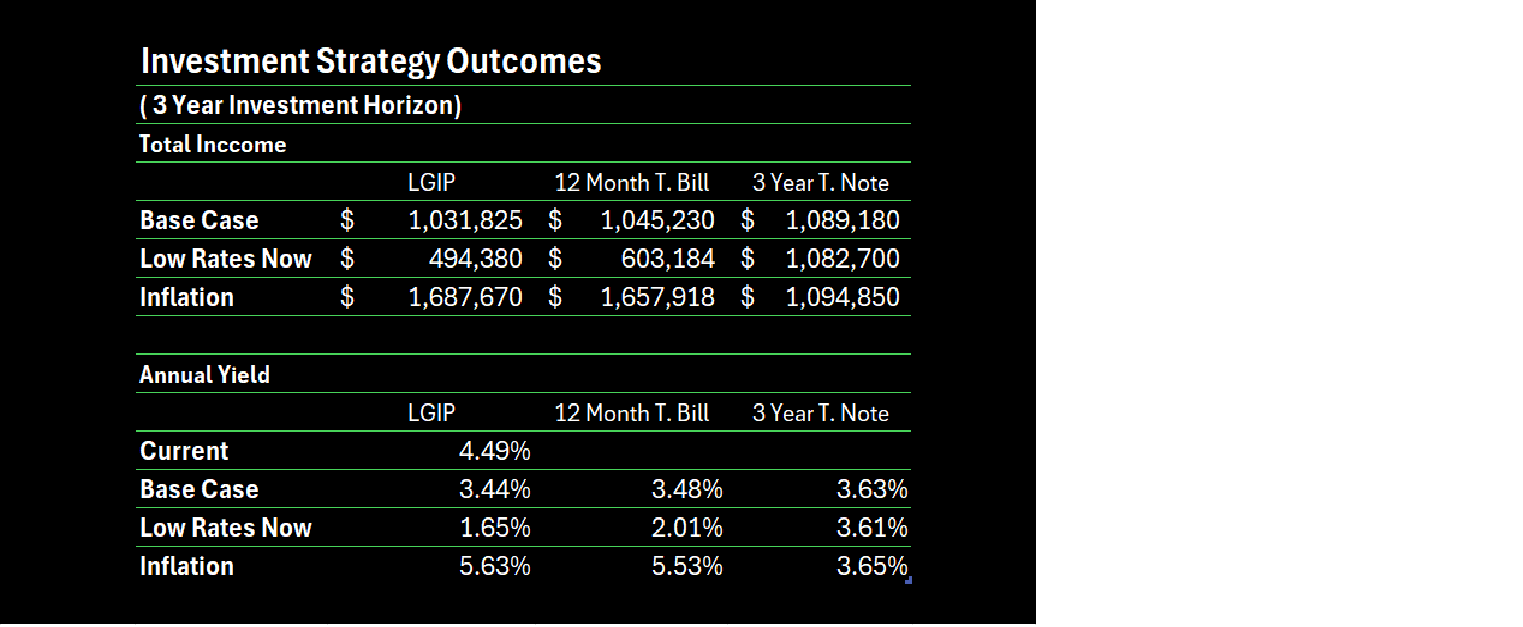

Results are shown on the table below. The base case is for the federal funds rate to fall from its current level of about 4.30% to 3.00% over the next 18 months. LGIP rates will track lower, but with a lag related to their weighted average maturity and the yield on 12-month Treasury bills will decline from the current rate of 3.85% to a rate of 3.20% two years from now. An investment in the three-year Treasury note will be fixed at its current yield of 3.60% for its life.

Investment maturity does not greatly affect results in the base case. The difference in annual yields is 19 basis points, about $57,000 over three years on a $10 million investment. If you were certain that the base forecast would be realized it would be relatively easy to select the option. Immediate liquidity (via the LGIP) and upside potential if rates do not fall to these levels or actually rise would cost potentially less than $20,000 per year (in foregone interest) on a $10 million investment. You might think about this as liquidity and rate insurance, with the lower interest earnings akin to a small insurance premium.

Next consider the possibility that Trump’s “reduce rates now!” happens. Lower rates have a drastic impact on LGIP earnings, cutting them by about $537,000 over the three-year period. The impact on a one-year strategy is to reduce earnings by about $442,000. The impact on the three-year investment is limited to a small amount of reinvestment risk.

If inflation rises, leading the Fed to tighten policy in the out years the LGIP investment and one year investment both do much better than in the base case. Higher rates DO mean more interest income!

Bottom Line

The path forward is uncertain. If intertest rates move lower along the path forecast by the Fed and implied by current market rates the result will be manageable. Public funds portfolios will continue to earn income at rates that are high when compared with the overall levels for this generation. But the tail risk—the risk that the path will veer from this-–is significant and the impact on investment income could be notable. Longer duration investments offer protection from this uncertainty if rates move sharply lower, but they reduce the potential to earn more income if inflation leads to higher rates a year from now. By how much? The scenario analysis provides some insights into this.

Portfolio managers cannot know what the market will do, but they should evaluate their portfolio strategies along multiple interest rate paths to be confident their constituents, CFOs and governing boards, are on board with their strategies.