A New Bank Capital Rule: Why it Matters

In a nation of more than 4,500 depository institutions, why should it matter that Federal regulators have proposed a narrow rule that applies only to eight?

In a nation of more than 4,500 depository institutions, why should it matter that Federal regulators have proposed a narrow rule that applies only to eight?

- The rule, proposed at the end of June by the Federal Reserve and other bank regulators, would ease the requirement that the largest banks maintain a capital buffer, with the expectation that this would lead them to buy and hold more Treasuries and to maintain liquidity in the bond markets in times of stress. The proposal would reduce the capital requirement for banks engaging in buying, holding, and trading U.S. Treasuries that the regulators view as low risk.

- This marks a change in direction by regulators responding to demands of the Trump administration that bank regulation be eased. While it affects only eight banks and only one business segment, bankers see this as the first step in a broader effort to address their concerns that they are over-regulated.

- Proponents believe the change will encourage banks to support the capital markets, particularly in times of stress, while others see a weaker capital base raising the risk that the government would have to step into the markets during times of stress.

- While one factor behind the proposal may be the change in tone in Washington from “prudent regulation” to “regulation roll-back” another is the prospect of continued growth in Treasury issuance that will require more efforts to fund this expanding national debt.

The details.

To understand the impact of this proposed rule you might think of banking as two businesses.

One is based on gathering deposits and making loans. My first bank account was a passbook savings account with the Peoples Bank for Savings in New Rochelle, NY, an institution that had perhaps $50 million in assets. It gathered insured deposits, transformed them into mortgages and loans, and distributed the net margin (“profit”) to its depositor shareholders. (It was a mutual savings bank.)

Peoples Bank for Savings is long gone, but the business line, gathering deposits and transforming them into loans, is still an essential bank business. But it’s been overtaken in many respects by a second business, market making, that has received the highly publicized attention of regulators in recent years as the Federal Reserve (and other bank regulators) wrestle with how to prevent massive bank failures that end up requiring government intervention and tanking the economy (a la 2008).

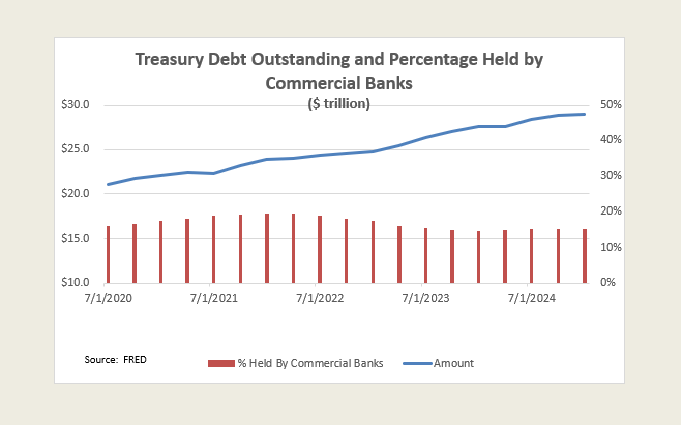

This is a business dominated by the eight global systemically important banks (“G-SIBs”). It is a capital markets business rather than a deposit-taking one. For perspective on this second line of bank business consider this: The G-SIBs account for about two-thirds ($16.1 trillion) of overall commercial bank assets, they issue the lion’s share of all commercial paper and the largest share of investment grade corporate bonds and own 15% of outstanding Treasury debt.

While most banks still employ a modern version of the Peoples Bank business model (but without pass books) the industry and its leaders are dominated by the capital markets business. One other observation related to scale: the largest G-SIB, JPMorgan Chase has $4.3 trillion; their assets alone are equal to about 15% of the total economic activity of the US.

The nature of the financial system framework has made systemic risk a big focus, with the tension between those who think government regulators should call the shots and those who believe that market forces will be better. All of this is complicated by the history of bank failures that have destabilized markets and caused economic activity to collapse.

Breaking up the largest banks might appeal to some, but it would disrupt the financial markets that have come to depend on G-SIBs to underwrite and trade, particularly in Treasuries. The volume of outstanding Treasury debt in public hands has leaped from $17 trillion to $29 trillion in the past five years, and it’s bound to grow in the next decade. The Treasury market trades about $1 trillion a day. Without the G-SIBs, how would the capital markets function? The answer is likely “not very well.”

Requiring that banks cover risk with capital seems like a natural, but capital is expensive. Shareholders expect equity-like returns to invest their money in bank stock and banks pass this cost on to borrowers and those who buy financial services (custody, payment services, etc.). It seems obvious that not all bank business lines have the same risk (compare lending with payment services, for instance). So why should a bank that offers payment services be expected to have the same capital ratio as one that lends to hedge funds?

OK, then, how about scaling capital to risk? That may seem to be an obvious solution but it’s far from straightforward. For one thing, how does one scale the risk of a payments business compared with a trading business? For another, do similar businesses at different banks have the same risk, or are some less risky (or operated in a less risky manner)? And how do you scale this?

There are no easy answers to these questions. Regulators do studies, apply judgements, and come up with capital requirements. Banks push back, arguing that they are the best judges of risk and that, if they are wrong, their shareholders will pay the price.

The bankers’ position is true—to a point. If the bank is large, though, and it makes bad business decisions, its failure could disrupt the economy and require government intervention (aka a bailout) to avoid economic catastrophe. Think this can’t happen? Think 2008 (or 2023 with the failure of Silicon Valley Bank whose assets were only about one percent of total commercial bank assets when it failed).

Global bank regulators have been wrestling with this problem for nearly 15 years, publishing a framework in 2011 (Basel III) with minimum requirements for capital, and in 2017 a set of reforms to strengthen the banking system (the so-called Basel III Endgame). No surprise that in the U.S. implementation is complicated by the politicization of decision-making. “Tailoring” capital and liquidity rules was favored during the first Trump presidency. President Biden’s term ushered in proposals to expand them, and the second Trump presidency has been accompanied by another pull-back.

With a history of push forward, fall back, push again the move by the Federal Reserve and other regulators at the end of June to revise an obscure rule on bank capital takes on new significance. It’s the first of a series of regulatory initiatives that could remake the regulatory environment for the banking industry.

The supplemental leverage proposal (available here) would loosen a requirement that the nation’s largest banks set aside capital to support their holdings of what are generally considered to be risk-free bonds—U.S. Treasuries. Treasuries are not generally thought to have credit risk for U.S. investors, and if they are held to maturity losses that might be accrued (but not realized) because of changes in interest rates need not cost the bank money. This view might lead to the conclusion that the capital is there to buffer the overall capital of a bank to support its other businesses including business, consumer, and mortgage lending, rather than to support ownership of risk-free Treasuries.

Perhaps, but banks that own Treasuries on a risk-free basis are unlikely to make money doing so. Treasuries do not normally carry interest rates that are higher than those offered by banks for deposits or debt obligations sold by banks to raise funds, so to create margin a bank would have to leverage assets against liabilities or mis-match asset and liability maturities to create arbitrage. Each of these strategies entails risk.

There is also the matter of finding buyers for the increasing supply of Treasuries. Banks, with $18 trillion of deposits, seem like a good place to look. Some say that the eased capital requirements will encourage banks to buy and hold Treasuries. In this context it should be noted that bank holdings of Treasuries more than doubled from $2.2 trillion in 2020 to $4.5 trillion in May. As the above chart shows, banks have maintained ownership of 15%-16% of the growing Treasury supply, expanding their ownership as the volume of Treasury debt has grown. At some point pushing to incent banks to add Treasuries will crowd out other potential borrowers. We may not be there yet, but that possibility is one way that growing Treasury debt can become a drag on overall economic growth.

Winners and Losers

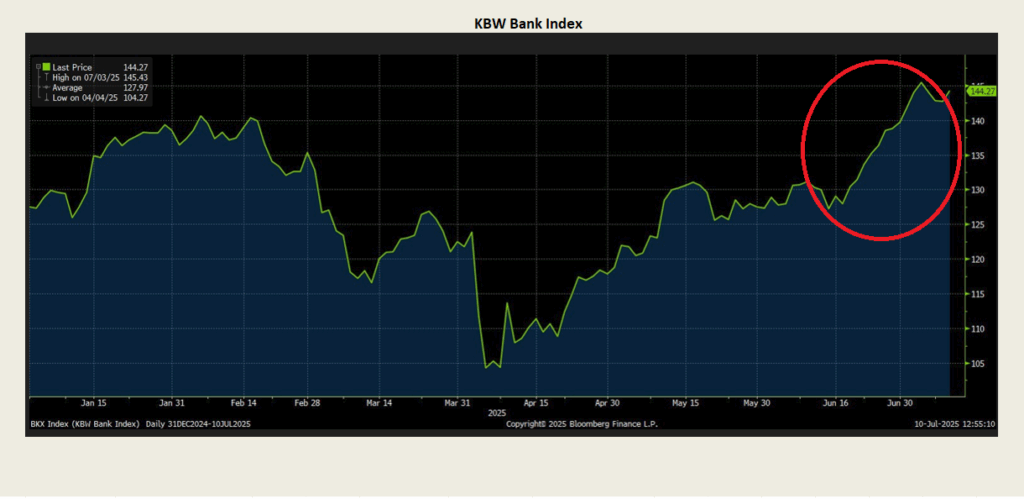

Bank shareholders appear to have been winners in the latest move. A broad index of bank stock zoomed up as the intent of the Federal regulators became known in June.

Other winners might be those who participate in the Treasury market, including state and local governments whose Treasury holdings represent 40% of their overall investment assets. Improved liquidity and lower cost to banks of carrying securities in trading accounts could help all investors in a stable market. Thus, SIFMA has come out in favor of the proposal.

Meanwhile reducing the capital buffer requirement is not a bond-friendly move. It’s not that it is or should be a major credit event for bond holders. It’s just that for those that invest in debt obligations (commercial paper, bonds, etc.) more capital is better. Not to be myopic on the topic, but bond holders should have a different perspective on bank returns on capital than shareholders.