An Update on Privatizing Fannie and Freddie

There is nothing like a Trump Truth Social post to grab attention. That was the result when an AI generated image of the President ringing in a listing of stock of the Great American Mortgage Corporation (Ticker “MAGA”) 10 days ago put the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in play. These government sponsored enterprises, once representing major holdings of public funds investors, still appear in state and local government portfolios—though in diminished size—and their future is now up in the air with the administration and some market participants pushing for privatization. This could disrupt the housing sector and the GSE markets, so best to pay attention.

There is nothing like a Trump Truth Social post to grab attention. That was the result when an AI generated image of the President ringing in a listing of stock of the Great American Mortgage Corporation (Ticker “MAGA”) 10 days ago put the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in play. These government sponsored enterprises, once representing major holdings of public funds investors, still appear in state and local government portfolios—though in diminished size—and their future is now up in the air with the administration and some market participants pushing for privatization. This could disrupt the housing sector and the GSE markets, so best to pay attention.

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were once dominant issuers in the money market and short term investment grade space. In 2007 their outstanding debt—not including mortgage-backed securities—totaled about $1.6 trillion accounting for more than half of the universe of short-term government obligations. To maintain this share of the market they paid 10-20 basis points more in yield than Treasuries. They often made-up half or more of the portfolios of risk-adverse public funds investors. (Mortgage based securities issued by the GSEs totaled much more in volume but represented a small component of public fund investments.)

- The two GSEs became insolvent in 2008 and have been in conservatorship since, supported by nearly $200 billion of U.S. Treasury investment. While their outstanding debt, consisting of discount notes, floating and fixed rate notes is much reduced from the level prior to conservatorship, they have grown their presence in the mortgage market, accounting for nearly $7 trillion of residential mortgages outstanding.

- Privatizing the two mortgage giants has been an elusive goal that involves competing interests: the current value of the government’s investment ($300 billion or more), the central role Fannie and Freddie play in the mortgage market, and the desires of Washington and affordable housing advocates to stimulate the housing market.

- Public sector investors should not expect a return to the times of plentiful short term GSE debt. The creditworthiness of currently outstanding debt obligations should be preserved, but privatizing will lead to changes in the structure and credit of the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac obligations. Their status as government agencies and implied credit backing is likely to change. Outstanding debt should be safeguarded, but the changes could well lead to loss of “government agency” status and with that the ability of many state and local governments to invest in these securities in the future.

The details

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are financial market mainstays, founded in 1938 (Fannie) and 1970 (Freddie) to support residential mortgages. They grew, became publicly held, then collapsed in the Great Recession, leading to a government bailout and conservatorship. Their prominence and size made them truly too big to fail, but in the last 18 years they have continued to grow a share of the markets and today their primary business, packaging and re-selling residential mortgages, accounts for about 55% of the residential mortgage market.

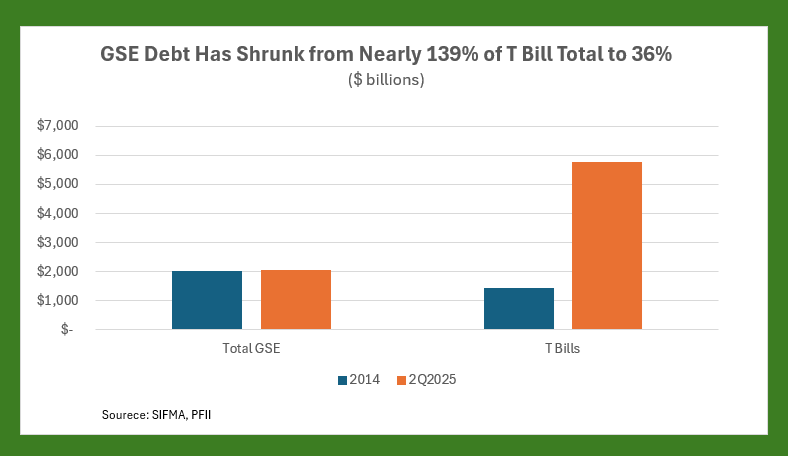

Before their fall the two were also major issuers of short-term debt: discount notes (similar to Treasury bills and commercial paper) and short- and medium-term notes/bonds. Initially proceeds were used as working capital, but over time their management realized that the implied support of Uncle Sam gave them a borrowing advantage, and they used this to build a large, leveraged, and risky business arbitraging opportunities in the mortgage market. At its peak this led to $1.6 trillion of outstanding debt, much of it sold to corporations, money market funds, LGIPs and public agencies. In 2007 the total outstanding debt of the two was about 150% of the total Treasury bills outstanding!

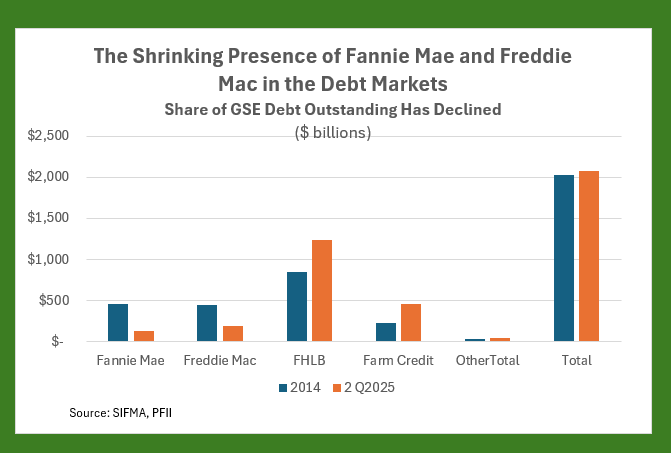

Today Fannie and Freddie have a much-diminished presence in the debt markets. Outstandings total $329 billion. For comparison Treasury bills outstanding are about $6 trillion so GSE debt represents about five percent of the government money market universe, excluding repurchase agreements. (For the full story, other GSEs, principally the FHL Banks and Farm Credit System filled the space left by Fannie and Freddie, so the total debt from all GSEs, $2.0 trillion, stands at about the same level as it was in 2007 and 2014.)

Today Fannie and Freddie have a much-diminished presence in the debt markets. Outstandings total $329 billion. For comparison Treasury bills outstanding are about $6 trillion so GSE debt represents about five percent of the government money market universe, excluding repurchase agreements. (For the full story, other GSEs, principally the FHL Banks and Farm Credit System filled the space left by Fannie and Freddie, so the total debt from all GSEs, $2.0 trillion, stands at about the same level as it was in 2007 and 2014.)

The move from abundance to scarcity is most noticeable with regard to interest rate spreads. Where once discount notes paid ten to 20 basis points more than comparable Treasuries and constituted a majority of short term public agency portfolios, today the explosion of short term Treasury bills—up from $900 billion in 2007 to about $6 trillion today—and liberalized public sector investment policies that accommodate credit instruments have led to a shrinking GSE holdings in public sector portfolios. These days spreads in the low single digits are the norm and often there is no spread unless an investor takes additional interest rate risk by holding a callable or step-up GSE obligation.

Meanwhile the role of the GSEs in the residential mortgage market has grown. With a continuing focus by Washington on the high price of housing that has put ownership out of the hands of many middle-income Americans and the multiplier effect that housing construction has on other sectors of the economy some political leaders are pushing privatization as a way to boost the sector. Others have warned that privatization would raise interest rates on residential mortgages to provide the income needed to support the capital structure of a privatized entity. (Most privatization plans would consolidate Fannie and Freddie into a single company.)

Privatization is a priority of the Trump administration, and some forms could be accomplished without Congressional action. The pending expiration in September 2028 of the government’s warrants on 80% of the equity of the companies reinforces a current timeline. And the possibility that the government could realize up to $300 billion or more for its ownership is surely a factor.

The distinction between debt securities and pass-through securities is important to have in mind because privatization is likely to affect the two forms differently. We estimate public agencies hold around $100 billion of the debt securities of Fannie and Freddie. While that and total outstanding debt securities at $329 billion is a large number, they are not a big consideration in discussions. Privatization will focus on the security and liquidity behind the MBS market, bearing in mind that credit and liquidity will affect the entire $13 trillion residential mortgage market. It will also focus on creating a public market for the equity of the new entity. Public funds hold a small share—we estimate less than $100 billion—of the $7 trillion of MBS securities issued by the GSEs. In a sense, public entities will be along for the ride.

There is no published Trump Administration plan for privatization, but Project 2025, the roadmap for much of what the Administration is endeavoring, calls for them to be “wound down.” An influential proposal from Bill Ackman, a hedge fund manager who has taken a lead role in pushing for privatization (and has a big investment position that would benefit from the move) calls for public issuance of equity, providing a government backstop for the company and setting modest retained capital requirements. His proposal recognizes that exemption from Securities and Exchange Commission registration and preferential treatment for bank capital purposes would end if the entity morphed into a corporate issuer.

The key to privatization is likely to be to provide a backstop for MBS issues in a manner that results in a favorable rate for the underlying mortgages. How the backstop will be structured to satisfy investors while maintaining the principles of a private entity is not clear. But unless this can be accomplished future issuances will be viewed as no different than current commercial mortgage-backed securities and this would result in higher pass-through interest rates. In all events to provide the backstop to debt instruments would seem to conflict with the objective of privatizing the companies.

The likely outcome of this effort would be to “grandfather” the rights of debt holders as of some future date and allow the post-privatized company to fund its working capital needs with what will be commercial paper and corporate bonds. Future holders of this debt would then look at the credit protections and risks of the new entity or entities.

Key take-aways for public agencies

- Privatization is likely to end the government agency status of the GSEs or successor organization. Fannie and Freddie are now exempt from registration under the Securities Act of 1934, receive preferential treatment by regulators for bank capital requirements and receive preferential tax treatment in some states. These characteristics afford them the designation as federal agencies or government sponsored enterprises and are the basis for their legality under many laws affecting public funds investments. Without that they are likely to be deemed corporate or other non-government obligations.

- Loss of GSE status has implications for investment policies. In some cases, holding the debt may not be legal. Holdings concentration and maturity limits will be implicated. So will collateral requirements for bank deposits and repurchase agreements.

- The working capital debt of the organization(s) after privatization is likely to look very much like that of an investment grade corporate entity—that is, it will issue commercial paper (to replace discount notes) and bonds/notes that are backed by its corporate credit. A guess is that they will be structured to gain investment grade ratings (think “A”). Public agencies may consider investing in these, but not under the heading of government sponsored enterprise issuances.

- The credit behind the currently outstanding debt obligations is TBD. It’s not likely to be stranded or allowed to deteriorate, but it bears close monitoring because sometimes strange things happen.

- Liquidity for Fannie and Freddie debt obligations could deteriorate, with wider bid/offered spreads and liquidity disappearing when markets are stressed. The best way to think about this is to look at the behavior of commercial paper and corporate bonds under these circumstances.

- If Fannie/Freddie go by the wayside, the overall effects on public funds investment portfolios should be small because their contribution to portfolio returns in recent years has been modest. We’ve already observed that discount note margins compared with Treasury bills have been small, if any. Bloomberg calculates the average yield difference between three-month bills and discount notes in the past year as being seven basis points in favor of bills.

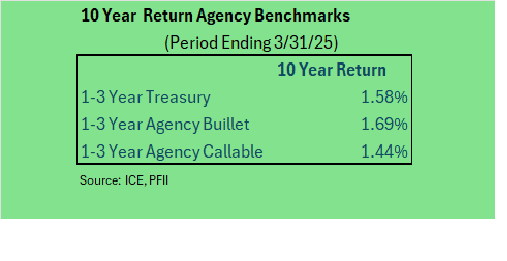

For longer maturities, the accompanying table summarizes results of an analysis over the ten years ending March 31,2025. A benchmark of agency bullets in the 1-3 year maturity range out-performed Treasuries by 11 basis points. A callable Agency benchmark with similar tenor under-performed by 14 basis points. Even 11 basis points should be discounted by the probability that a portfolio would hold much less than a majority of its portfolio in these securities.

For longer maturities, the accompanying table summarizes results of an analysis over the ten years ending March 31,2025. A benchmark of agency bullets in the 1-3 year maturity range out-performed Treasuries by 11 basis points. A callable Agency benchmark with similar tenor under-performed by 14 basis points. Even 11 basis points should be discounted by the probability that a portfolio would hold much less than a majority of its portfolio in these securities. - In some cases, statutory language related to investments, investment policy language, collateral requirement descriptions or bond document language may have to be addressed if privatization proceeds. Most state statutes and investment policies permit investment in debt of these issuers, often by including language authorizing investment in “federal agencies” or “government sponsored enterprises,” but some policies specifically name the agencies. The reference to specific issuer names could become problematic after a reorganization/privatization.