Cracks Are Appearing in the Credit Markets

Cracks are appearing in the credit markets and public funds investors should amp up risk management efforts or avoid the risks that could upend portfolio strategies at a time when economic uncertainty, falling short term interest rates and disruption to historic government funding could stress state and local government budgets.

Cracks are appearing in the credit markets and public funds investors should amp up risk management efforts or avoid the risks that could upend portfolio strategies at a time when economic uncertainty, falling short term interest rates and disruption to historic government funding could stress state and local government budgets.

There are two stories here: a spike in credit stress indicators in some market sectors and the risk of supercharged artificial intelligence assets vs. a story of broad credit market complacency.

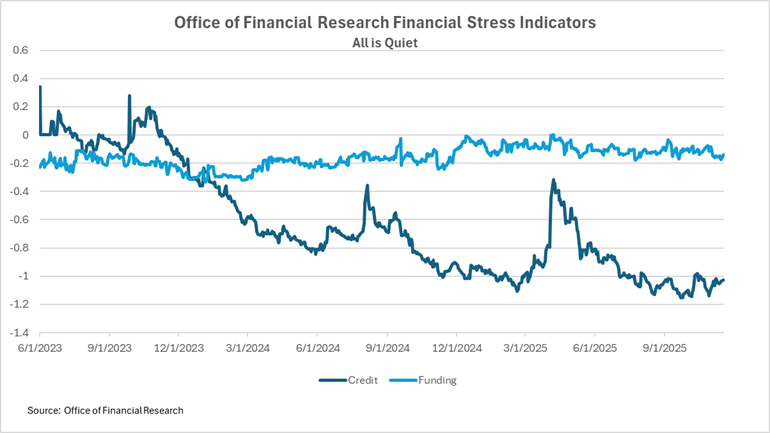

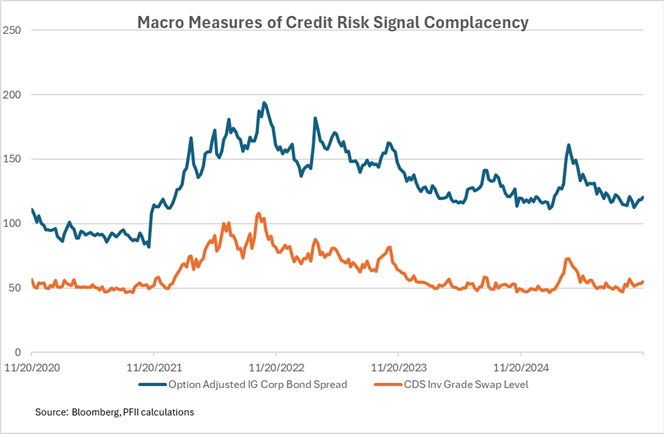

The complacency story is illustrated by the Office of Financial Research financial market stress monitor and specifically its credit measures, shown below. It reports macroeconomic stress levels that are well-contained.

But there is a compelling credit stress story.

• Think of credit as a surface on a shiny ball that is the macroeconomy. Cracks on the surface could impact the mass of the ball, or an eruption from within could shatter the surface. Signs are that we are nearer the first than the second of these events, with stresses growing on the credit surface that could degrade the underlying economy.

• Weakness in credit is not universal. Some segments of the credit market, such as major bank lending, appear strong. Also strong are the fundamentals of the large publicly traded companies that support the public bond market. But other elements—consumer borrowing, private credit and borrowing to support artificial intelligence efforts—are showing signs of stress.

• The risk is that these weak points could metastasize into a broader challenge to the credit markets or even into a kind of credit freeze that drags the economy down.

• Public agencies’ assets for the most part are not directly exposed to the segments where credit cracks have appeared (although public agency pension accounts may be vulnerable). But problems in credit could disrupt the fixed income markets more broadly and lead to (temporary) loss of liquidity and market value for bank and corporate bond investments. They could also raise concerns among the public about the way government assets are invested. These are reasons to be cautious and to follow a defensive strategy when it comes to using credit instruments in public unit portfolios.

Deep Dive

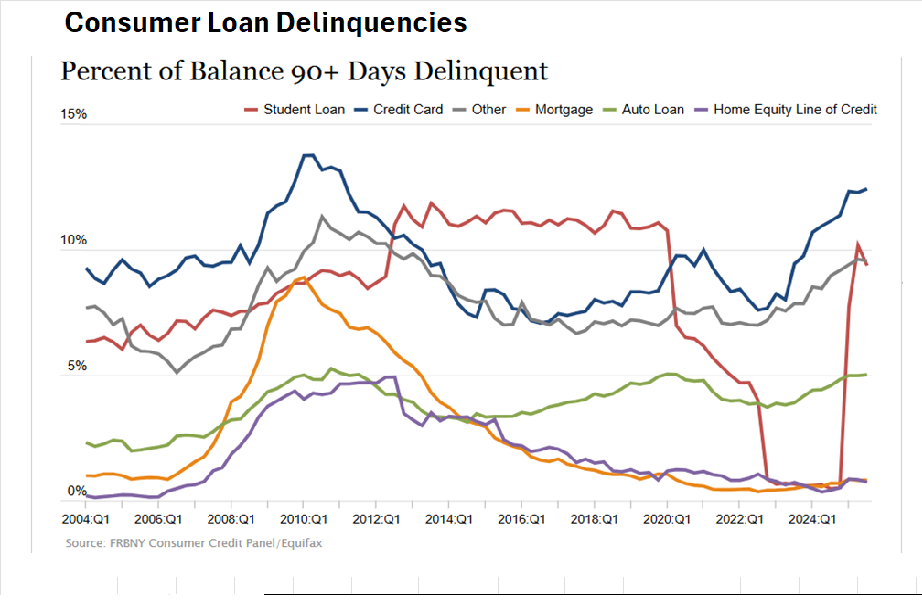

First let’s look at the signs of credit stress. They are manifest in the consumer loan space where the Federal Reserve reports that loan delinquencies have risen to levels not seen since the Great Recession.

This is true of credit card, auto loan and student loan debt Securities backed by these loans (asset-backed securities) are structured more carefully these days than they were in 2007 and 2008 when they were a leading edge of the credit crisis, but it’s possible that a particular issue becomes impaired. You may avoid direct exposure, but bad headlines would depress the market values and liquidity of a broad class of securities.

Inflated home values and leveraged lending in the mortgage market were causes of the 2008 crisis. At this point, the residential mortgage market shows no signs of stress, with delinquency levels low (See chart above). Consistent price appreciation of residential real estate means that mortgages tend to have collateral (the residence) that is valued in excess of loan amounts. It helps, as well, that a housing shortage supports demand for housing.

The same cannot be said about the commercial real estate market which is under some stress. “Protective” structures and top credit ratings go only so far, as the holders of AAA rated bonds in a suburban New Yorek City shopping mall learned recently when their investment paid out only 70% of par.

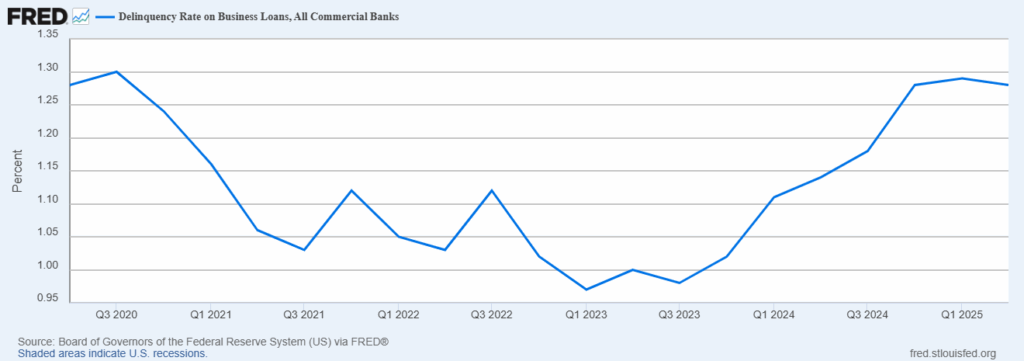

Delinquency rates on business loans by banks are also elevated (see below chart) to levels not seen since the pandemic.

But bank credits do not appear to be stressed. Banks have higher capital buffers than they had in 2008. That may change with the move to ease bank capital requirements, but for now the buffer that protects unsecured bank deposits and bank notes/bonds is stronger than it has been in the recent past. And like it or not, some banks are simply too big to be allowed to fail. That’s not to say you wouldn’t suffer criticism and bad publicity for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, but at the end of the day investing in obligations directly backed by the mega institutions probably means “money good” no matter what.

Regulatory oversight and capital requirements don’t protect investors in private credit, the shadow banking system that has funded some of the headline-making borrowing for artificial intelligence data centers and power generators. Some market observers have warned that the opaque nature of this lending, the complex financial structures that support it, and the lack of market-based valuations could spell trouble. It is unlikely that public agencies have any direct exposure to these sorts of risks, but any disruption of the private credit markets is likely to reduce liquidity and depress market values across the universe of credit instruments.

Ratings agencies have not raised alarms about credit deterioration. While Moody’s calculated that the probability of default for all listed U.S> public companies is 9.2%, the agencies have spent several years upgrading more credit issues than they have downgraded. Last year the three main agencies upgraded about two credits for every one they downgraded. And the ratio in the current quarter is 1.66:1, so no storm warnings from them. In fact the agencies have been generally supportive of the huge borrowings by the AI leaders that have grabbed financial news headlines and stirred some industry leaders (Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan who warned recently of financial “cockroaches” in consumer lending; bond wizard Jeffrey Gundlach of DoubleLine who said last week he preferred cash to credit as an investment.)

Of course the rating agencies failed to provide timely warnings of the 2008 credit meltdown, but that was then.

The final observation is that markets are slowly awakening to this renewed risk. Market-based risk signals have grown somewhat louder over the past couple of months, but credit cracks are only beginning to be reflected in prices and interest rate spreads.

A broad measure of this is the index of investment grade corporate bond spreads (see below). It measures the additional yield that investors receive for the market and liquidity risk of investing in credit. It is now at about 120 basis points. Earlier this year, as President trump announced his tariff strategy it rose to more than 170 basis points. During the Covid lockdown it peaked at 250- basis points.

Until a month ago the cost of buying protection against broad credit defaults was near its 15-year low, and today it is below average. (The spread at this writing is around 55 basis points; it has ranged from 45 to 145 in the last 15 years.)

If/as credit cracks suffuse the market spreads are likely to widen, depressing market prices for corporate debt and raising the premium to be earned for those who venture in.

Public agencies could avoid investing in a credit that becomes impaired, and they may not take mark-to-market values into effect in reporting earnings but that’s not to say their investment strategies are immune from criticism if they experience unrealized losses.

What’s it Worth?

Investors who employ credit in a cash-type portfolio can expect to receive 20-25 basis points more than limiting investments to government obligations on that portion of the portfolio. That seems like a healthy chunk, but if you limit credit to 30%-40% of the portfolio, as do prime institutional money market funds, the net benefit is six to ten basis points. It’s not nothing but on the other side of the ledger there are e costs in time, other resources, and risk.

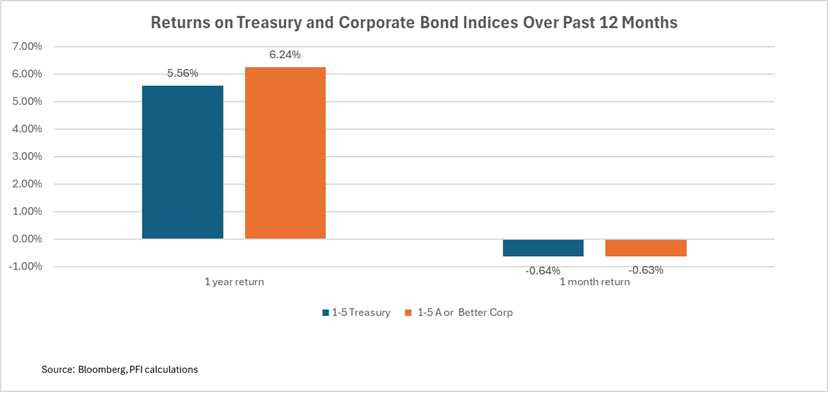

Similarly, for separate accounts an index of one-to-five-year Treasuries returned about 5.56% over one year, compared with a return of 6.24% for an index of AAA-A rated corporates.

If 30% of your portfolio were invested in credit this would equate to an overall benefit of about 20 basis points. And recognize that it doesn’t take a big move in the market to eliminate this benefit. In the past month, the modest widening of spreads has resulted in returns for the two indices that are about the same, so no net benefit.

Bottom Line

It is not that the credit markets have broken down, but the talk about unrecognized risk is louder today than it has been for a couple of years. The spread of credit yields to risk free yields doesn’t seem to reflect this changed amplitude. Risk is not just about loss of principal; it is also about fair compensation for taking on risk and the inevitable questions that come when investment portfolios are managed in the public sector fishbowl.