Is Monetary Policy Broken?

This may appear to be a bit wonky for some public funds investors who have more important things on their minds but bear with me. The implications of a breakdown in monetary policy are dire for investment markets and for the macroeconomy.

This may appear to be a bit wonky for some public funds investors who have more important things on their minds but bear with me. The implications of a breakdown in monetary policy are dire for investment markets and for the macroeconomy.

The headlines for next week’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting will be about rates. Will they or won’t they cut? But there is a far more important issue than whether the central bank does or does not cut rates by 25 basis points. It relates to how the central bank implements monetary policy and whether it has lost control of monetary conditions.

There are signs that policy is broken. Witness this:

• The obvious, if somewhat dated, sign is that the central bank fell behind in its efforts to combat rising inflation in the post-pandemic months. This led to sharp rises in rates in 2023 and 2024, heightened market volatility, loss of liquidity and market value losses for many portfolios.

• More recently we’ve had whiplash over expectations for the Fed’s move next week.

• Efficient policy should lead to short-term rates moving in concert, but recently they have become disconnected from the Fed’s main policy rate. While one has declined, others have not.

• FOMC members have taken to the streets, so to speak, to make their cases for monetary policy moves through an unprecedented surge in speeches to economic interest groups. Meanwhile President Trump, his administration and allies in Congress have raised loud voices in an effort to steer monetary policy. In a word, policy determination has been politicized.

Unpacking

The Fed has built its monetary policy around providing the market with forward guidance. For the past 20 years it has sought to signal its intentions, so investors have a chance to respond and provide feedback in advance of actions. Thus, the evolution of post-FOMC press conferences and the expanded schedule of speeches by Fed officials.

While this has grown financial literacy among households—these days folks other than economists can be heard chatting about the federal funds rate at dinner or in a bar—it has done nothing to strengthen the plumbing that makes monetary policy work. In fact, there are signs that the Fed is struggling to transmit its Fedspeak into the market. The tools it uses to implement monetary policy, opaque to all but a small number of bankers, traders and regulators who deal with an alphabet soup of rates (SOFR, OBFR, OIS, RRP, SRF) seem to have lost some of their edge, leaving the Fed less able to deal with market liquidity and bank stability.

Couple this with an emerging theme in Washington that regulators overreached in recent years and you have the makings of a policy breakdown. If so, uncertainty and market volatility could rise at a time when investors are seeking just the opposite.

Monetary Policy and Forward Guidance

Fundamental to the Fed’s policy is the concept of forward guidance and a toolkit to use its balance sheet and open market activities to transmit its actions smoothly and consistently across the market.

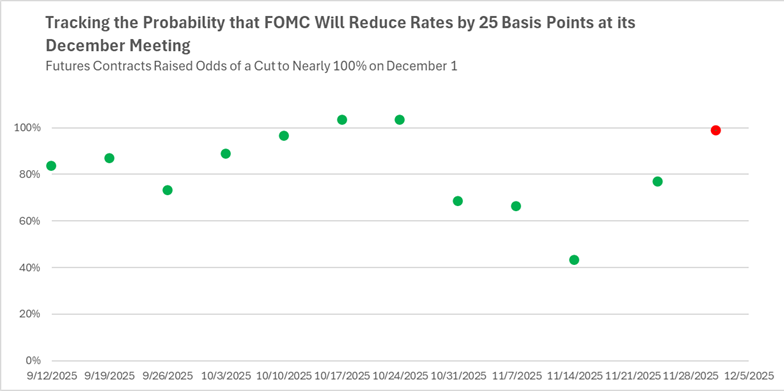

But forward guidance seems to have been lost. Case in point: the whipsaw of expectations for the Fed’s move at next week’s FOMC meeting. In the past month the market-based probability for a rate cut has gone from near certainty (right before the October FOMC meeting) to less than 50% (as investors reacted to Powell’s post-meeting comments) and back to near certainty.

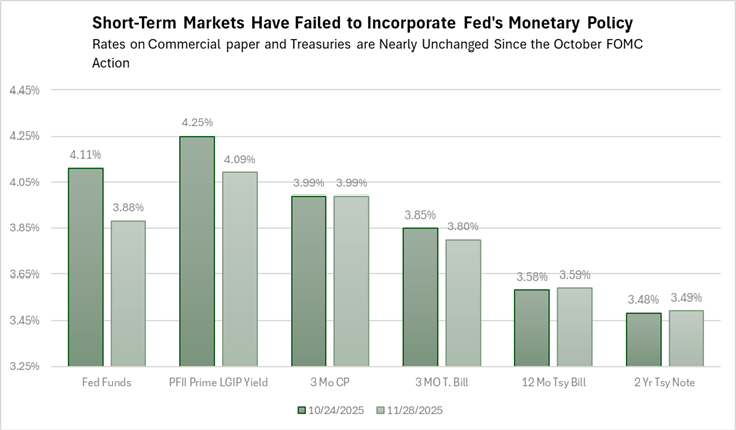

Meanwhile the policy transmission tools seem not to be working. This is illustrated by the behavior of the short-term markets in the past month. Its response to the FOMC rate decision in October was remarkable.

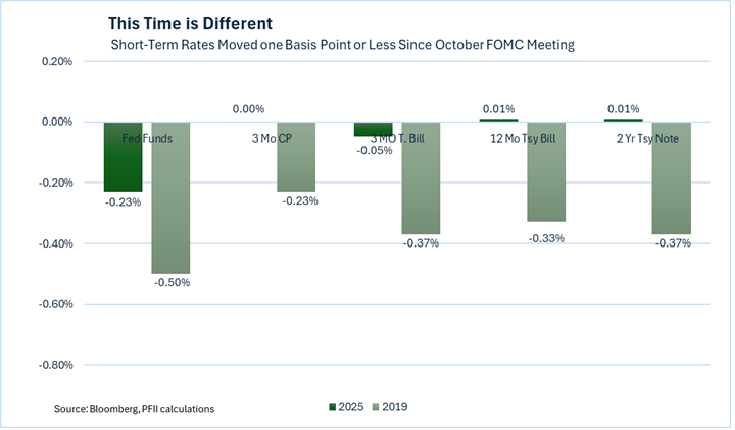

As the above chart illustrates, one would expect that a lower federal funds rate would bring down rates across the short-term markets in a consistent fashion. And if this were successful investors in longer-tenor securities would price them not just based on current short-term rates but also on expectations for rates in coming years. So, they too would come down.

In fact, when it reduced the federal funds target range by 25 basis points at its meeting on October 31, the market for federal funds responded as expected, with the effective federal funds rate at the end of last week dropping 23 basis points compared with the level the week before the October Fed meeting.

But rates on other short-term securities such as commercial paper, Treasury bills, and short-term year Treasury notes failed to follow. Rather they posted the same yields last Friday as they did the week before the last Fed move. There was no adjustment for the reduction in federal funds, nor was there any adjustment for the likelihood that the Fed will reduce rates by another 25 basis points next week.

This was not so when the Fed eased rates during the 2019 cycle. In July-October 2019 the central bank reduced the overnight rate by 50 basis points at two meetings and, as the following chart illustrates, other short-term rates followed.

They declined between 23 and 47 basis points.

In a few words, 2019 shows the market response to effective policy transmission; the current cycle does not.

Managing Market Liquidity

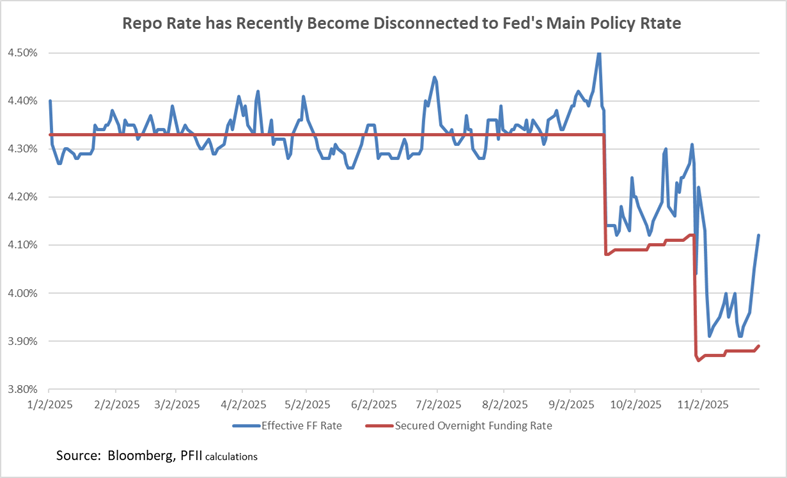

There is also evidence that the Fed is less able to manage market liquidity than in the past. Consider that federal funds make up a small share of the overall market. In a typical day their volume amounts to around $100 billion. Compare that to Treasury volume of over $1 trillion or repurchase agreement volume of around $5 trillion. In particular the central bank uses repurchase agreements to manage overall market liquidity,

As the accompanying chat illustrates, federal funds and repurchase agreement rates are normally closely tied. Between January and August 2025, the two rates averaged to the same figure. But since August the spread has shown unusual volatility.

This gives the central bank has less control over liquidity and bank reserves.

This is all a bit in the weeds for most investors, but it is front and center for the large banks and Treasury security dealers who have been forced to pay a rate premium and endure higher rate volatility in recent weeks to finance their positions in the repo market.

Bottom Line.

The sunny side of all of this is that higher (relative) repo rates and sticky yields on short-term securities like Treasury bills present an investment opportunity for public units. Elevated repo rates have supported LGIP yields since the October FOMC meeting, and they may well do so through the balance of the year. And the stickiness of short-term Treasury bill rates, which have barely moved in response to Fed easing, presents an opportunity for public funds investors of all sizes to invest for a term at rates that are not far from their levels before the Fed cut the funds rate in October.

But recent market behavior suggests the Fed has lost its audience. Chalk it up to the charge that the central bank fell behind the curve in fighting resurgent inflation or chalk it up to President Trump’s threats to the Fed’s independence or chalk it up to “technical factors.”

In the near time nimble (or lucky!) investors may reap rewards but in the longer-term market efficiency will suffer and it’s going to be more difficult to avoid stumbling.