Prime Money Funds: How Changes Could Affect Public Funds Investors

Plans by a little-known money market fund to alter its investment strategy could be a harbinger of changes to the industry that have significant implications for public funds investors.

The implications are three-fold: 1) state and local governments invest in money funds directly and some local government investment pools (LGIPs) invest in them as well, often as a substitute for overnight repurchase agreements; 2) LGIPs compete with money funds for public funds investments and changes in the money fund industry may lead to differing economics or risks when comparing them; and 3) there are implications for the short term fixed income markets where state and local government investors are major players directly and through LGIPs.

Let’s unpack this. The Capital Group Central Cash Fund has announced that by early June it will convert from a prime money fund to a government fund, giving up the ability to hold commercial paper and other credit instruments. It will thus avoid some of the money fund reform rules that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted in July 2023.

Capital Group Central Cash Fund is hardly a familiar name to money fund investors, although its $144 billion in assets represents more than 10% of the assets of prime money funds regulated by the SEC. The fund is not available to the public; it is one a of a small class of institutional money funds that provide a temporary parking place for cash managed by the Capital Group for its $2.5 trillion family of American Funds.

Prime money market funds were once a major force in the money management space. In 2014 they represented nearly $1.8 trillion in money fund assets, compared to $1.0 trillion in government funds. (The industry’s assets totaled about $3.1 trillion.) The SEC’s 2014 reforms, imposing redemption fees and gates, and requiring that prime institutional funds operate with a floating net asset value (NAV), led to massive shrinkage of prime funds as investors gave up the potential for somewhat higher earnings to avoid a floating NAV. Institutional investors withdrew nearly $800 billion in the months before the rules took effect. Retail investors, though they were not subject to the floating NAV rule, followed suit, withdrawing nearly $300 billion.

The changes wrought by the SEC’s 2014 reforms created clear distinctions between institutional prime funds and prime LGIPS, since the latter were not required to float their net asset values and they did not voluntarily adopt this policy.

The 2023 money fund reforms impose new liquidity requirements on institutional prime funds. Unless these are adopted on a voluntary basis by stable value LGIPs, the operating policies of institutional prime funds and prime LGIPs will diverge further. At first glance, a floating NAV with liquidity fees (the institutional prime money funds) compared to a stable NAV with no liquidity fees (LGIPs) may appear to favor LGIPs, but this would be true only if an LGIP is not subject to large scale redemptions in a volatile market—a possibility that the 2023 reforms are designed to address. True that historically LGIP assets have been more stable than those of institutional prime money funds (almost without exception). Will that stability continue? Time will tell.

The short-term credit markets. Institutional prime funds have a smaller presence in the short-term markets and prime LGIPs have a larger presence than a decade ago.

At their height institutional prime funds had total assets of $1.8 trillion and owned approximately $1.3 trillion of commercial paper and certificates of deposit/time deposits. This was estimated to be 75% of the supply in 2014. Their regular buying made these funds a major source of market liquidity, but also meant that if they stopped buying or became sellers because of accelerated shareholder redemptions their effect on the market would be notable.

Assets of prime money market funds fell to less than $700 billion when the 2014 reforms took effect. They have gradually recovered to reach just over $1.3 trillion this month. (Currently money fund assets are about $6.4 trillion.) Their character, however, has changed. Where retail investors accounted for an estimated 30% of prime fund assets in 2014, today they are more than half. Some analysts believe retail investor money is less likely to be “hot money” that reacts quickly to market events.

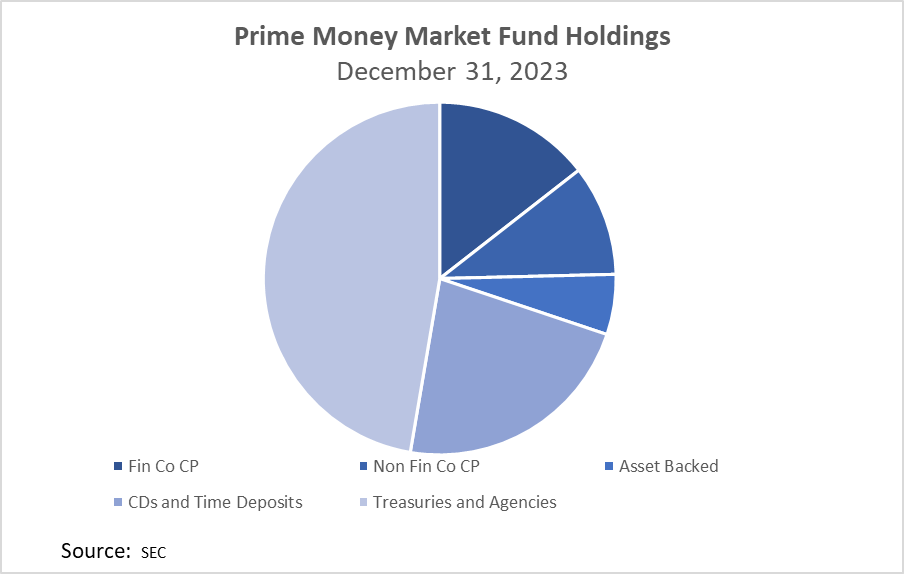

A decade ago, prime funds owned approximately $1.3 trillion of commercial paper and bank assets; today they own about $700 billion. The volume of these securities outstanding has expanded since 2014 from an estimated $1.8 trillion to $2 trillion. Today a little over half of aggregate holdings of prime money market funds are in commercial paper and negotiable CDs and time deposits. So, they are a smaller force but perhaps more reliable (?) market participant.

Other prime institutional funds may follow the lead of the Central Cash Fund in converting to government funds. The most likely are funds like the Central Cash Fund that are not available to the public. The assets of these specialized funds total about $300 billion.

The Bottom line:

- Public agencies that invest in money market funds are likely to use those that are government-focused, rather than prime funds since the floating NAV and liquidity fees are problematic for many government investors. A shrinking universe of institutional prime funds should not have a major impact on investment options used by public agencies.

- Prime-focused LGIPs are not subject to the SEC’s Rule 2a7 and do not offer a floating NAV or have liquidity fees. These LGIPs do not seem inclined to adopt the 2023 SEC reforms. Investors may see this as an advantage when compared with prime money funds, but investors seeking prime-based returns should understand that the SEC put forward the changes to protect investors from what might otherwise be unfair benefits and penalties of transacting share purchases and redemptions at a stable net asset value when underlying markets are volatile or illiquid (for example during the 2020 Covid lockdowns.)

- A diminished presence of prime funds in the commercial paper and negotiable CD markets could be felt, especially during periods of heightened volatility. This was most recently true during the Covid lockdowns. If institutional prime money funds follow the lead of Central Cash Fund and convert to government funds, this could result in less transparency and lower liquidity for the remaining players.