Sell America, Buy Gold

That’s a headline that is bound to grab eyeballs, but is there truth to it? And if so, what does it mean for state and local governments investors?

- Sell America is a great line for pundits that may have roots in financial market reality. Large and growing federal deficits could lead foreign investors to sell Treasuries and convert their proceeds from dollars to other currencies (or gold). This would push down the value of the dollar. Or the prospect of a weaker dollar in the future could cause investors to take their capital elsewhere or demand higher returns to invest in dollar-based assets.

- These results would pressure interest rates higher, and they could also boost inflation, though effects like this are likely to be slow and subtle (at least at first) and felt only over several business cycles. In the interim the usual forces that we are accustomed to—monetary and fiscal policies (hopefully) aimed at maximizing employment and managing inflation—should continue to be center stage.

Digging Deeper

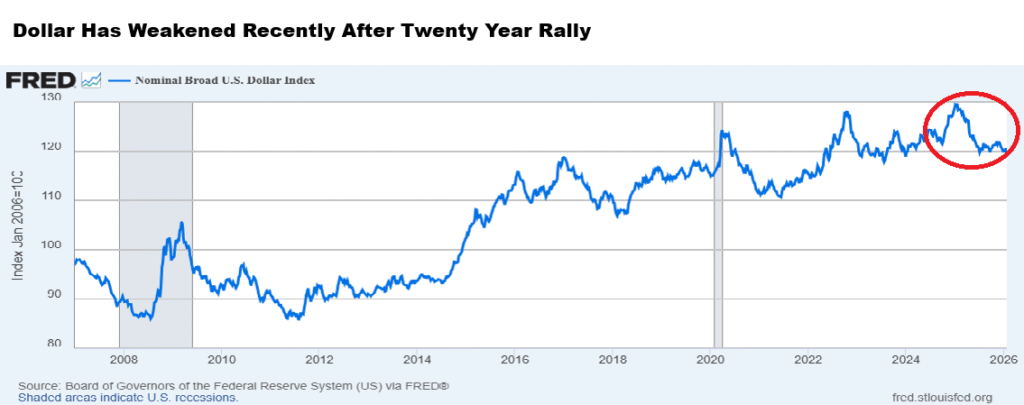

As the accompanying chart documents, the U.S. dollar appreciated over the past 20 years, boosted by a strong U.S economy and favorable investment climate.

The path peaked in December 2024. Since then, the dollar has lost about eight percent of its value. It’s not a big move when compared with moves after the Great Recession and Covid pandemic, but the move is notable because it took place as the economy posted strong growth compared to growth in other developed economies, long term government bond rates were elevated and the Trump administration touted tremendous commitments by foreign investors. All of these should result in a strong dollar. Yet the market said otherwise.

Selling America in the global markets could lead to foreign investors selling their holdings of Treasuries or directing the reinvestment of maturities into other instruments. This is unlikely to cause a short-term disruption of the market—the market is too large for that—and by selling they would hurt themselves.

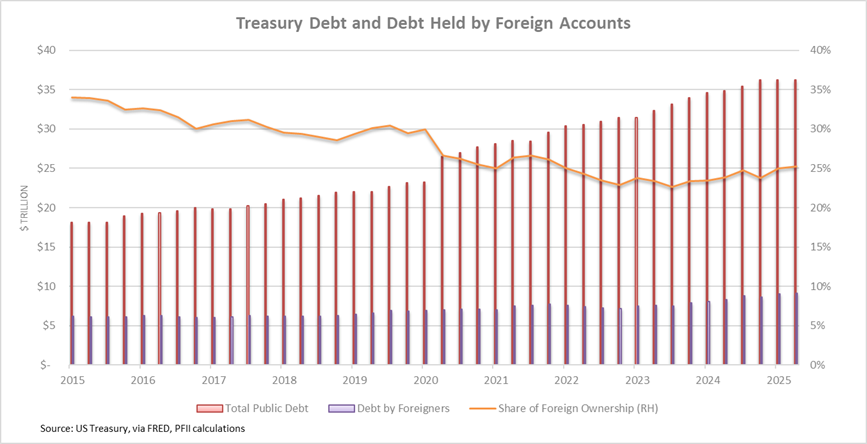

Foreign investors own more than $9 trillion of Treasuries, nearly 25% of the total outstanding.

While their ownership of Treasuries has grown their share of ownership has declined over the past decade as the sovereign debt load has expanded. That means the Treasury market is less sensitive to foreign investment today than it was 10 years ago. From time to time there are scary headlines that an unfriendly country (China?) might stop buying Treasuries as a foreign policy tactic. But China ownership accounts for only (!) about $800 billion, less than10% of foreign owned debt and about 2% of total public debt.

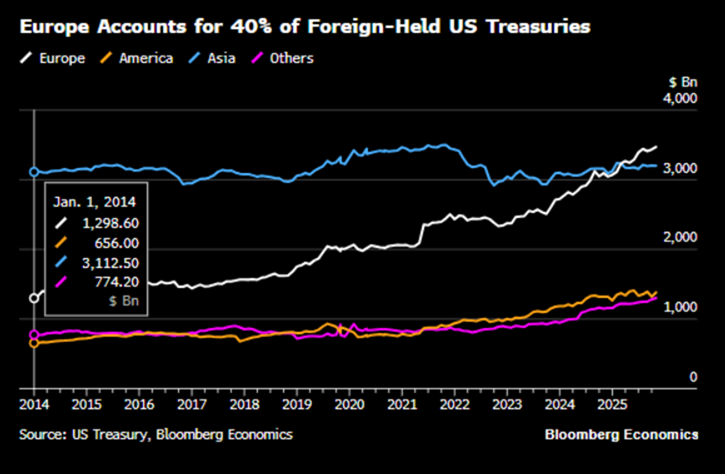

In fact, it is Europe that owns the largest share. Until recently most believed that the European Union was our partner for life, but perhaps the Davos meeting last week shook that faith.

Could/would foreigners stop buying Treasuries?

To answer this, consider how ownership of dollars relates to trade volumes and the balance of payments. In a few words, dollar reserves accrue to foreign accounts as a consequence of trade flows. A persistent global trade surplus with the U.S. has resulted in growing dollar reserves for foreign accounts. That is because foreign accounts acquire dollars when they sell goods and services to U.S. consumers. That’s the “balance” in balance of payments.

Foreign accounts either invest these dollars in dollar-denominated investments or exchange them for other currencies. For investment, Treasuries have been preferred because other dollar-denominated alternatives, corporate bonds or equities, would seem to be less secure than Treasuries. (Could the government default on Treasuries without affecting the broader bond or stock markets? Highly unlikely.)

Foreign investors could sell/ exchange their dollars for other currencies, but that would push down the value of the dollar. (Perhaps Liberation Day tariffs were a trailer for this movie.) That would depreciate the value of their dollar reserves and make their goods and services more expensive when sold to American consumers. That conundrum is behind the title of economist Kenneth Rogoff’s recent book on foreign trade economics, “Our Dollar, Your Problem.”

Continued growth of the federal deficit and international policies that foreign governments find distasteful may weaken the dollar. That would further roil the global economy, create forces of market instability and push interest rates on Treasuries (and other dollar investments) higher. (Higher rates would entice foreign investors to buy Treasuries; other dollar-denominated investments would have to adjust as well.)

Economists view this as a force of fiscal dominance or financial repression, terms used to describe policies that force the economic system to adjust to supporting sovereign debt at the expense of other things like consumption and private investment.

What if?

If foreign accounts seek to reduce their engagement with the U.S. it would be a long process that would not start with selling Treasuries. Disengaging would mean moving away from trade interdependence with the U.S. and seeking to establish an alternative to the dollar as the global currency of trade.

And along the way it would trigger significant devaluations of the dollar and other global currencies. Trump, in fact, mused about this in the early days of his second administration (remember the Mar a Lago Accords idea to threaten to weaken the dollar to boost U.S. manufacturing and re-structure Treasury debt held by foreign accounts?).

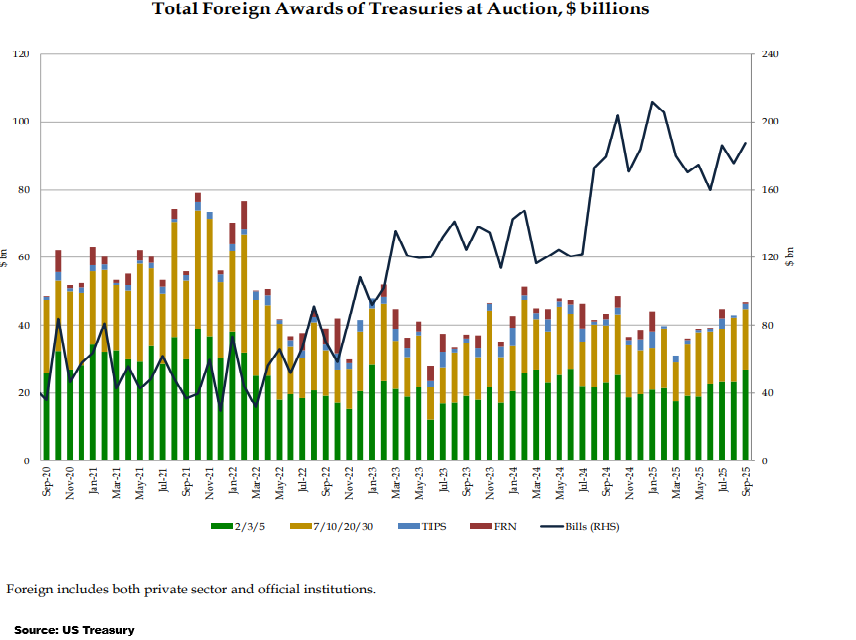

In the short term, foreign investors could also shorten the duration of their Treasury holdings, by buying Treasury bills instead of notes and bonds. This already is under way. As the budget deficit and Treasury funding needs have grown in the past five years foreign accounts have shown a preference for Treasury bills, with awards growing from around $20 billion a month in the immediate post-covid market to $150-$200 billion recently.

Which brings us to gold

If you are a foreign investor why not buy gold instead of Treasuries with excess dollars? You could think of gold as a multi-currency holding since it can be converted into any fiat currency, and if fiat currencies disappear it might once again be used directly to make payments.

At this writing gold is at a record high vs. the US dollar, about $5,300 per ounce. That’s roughly 80% higher than it was a year ago. Gold in Euros is up about 55% in the period. The difference is in part because the dollar LOST about 12% of its value vs. the Euro in this time. Another big factor, though, is that investors perceive risk and volatility of the dollar to be greater than they do in the Euro. So, the value of the gold “hedge” has appreciated vs. the dollar. That might not comport with the Trump administration’s report card on the U.S. economy, but it expresses the view of global investors, including sovereigns.

Over the last 100 years the gold standard was formally abandoned through agreement by central bankers. But in a notable way it’s crept back onto the stage. Central banks still hold gold reserves, and with the surge in gold prices the value of their gold holdings has eclipsed that of dollar reserves.

De facto return to the gold standard? Perhaps.

Bottom Line

If Selling America is a reality, it will not happen overnight or even in the short term—the typical horizon for state and local government investment strategies. Rather it will be the result of actions on many fronts over a period of years. Meanwhile short-term Treasuries should hold their value when measured against the dollar. (You could think of a Treasury bill as a dollar that pays interest and you would get the point.) And it’s possible that a continuing shift in foreign account activity will boost demand for short-term Treasuries (at the expense of longer-maturing bonds). That would lead to a steeper yield curve and upward pressure on mortgage and corporate borrowing rates.

And at the end of the day, it is against the dollar, or more properly a basket of the goods and services that governments buy that are paid for in dollars, that the results of investing public funds should be measured.

Well done