Waking Up to Lower Rates

Last week was supposed to be a big one for the financial markets, though perhaps not quite the way it turned out. A meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee and release of the monthly jobs report were on the schedule, and the smart money was betting that the Fed would pass on cutting rates, the jobs report would show a solid, if slightly weaker, labor market, and we’d all be able to check out a bit early for a summer weekend in July.

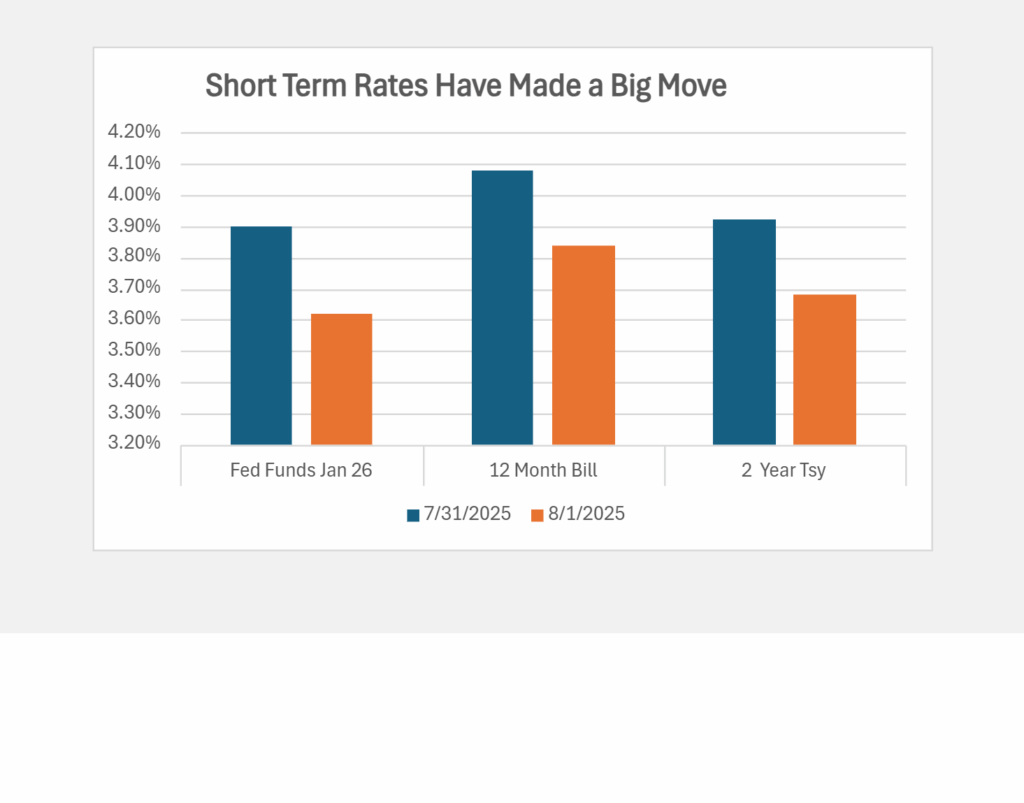

It did not work out that way. Instead, unexpected news, including large backward-looking revisions to the jobs figures, Trump’s summary firing of the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics which produced the figures, and the unexpected resignation of one of the seven Federal Reserve governors triggered a sharp rally that pushed rates down in one day by measures we don’t normally see more than once a year.

The effects of the jobs report are the most troubling/puzzling. Revisions to the figures for May and June changed them from signaling a resilient labor market to one that was weakening, and the July report amplified this. Most investors responded as if the revised figures show a true picture, but some followed Trump’s lead in arguing that the figures were politically-motivated. Whether this view was meant to convey that the economy was actually doing well or not was not clear.

The move in rates Friday and change in market sentiment were largely unexpected and therein lies an important lesson for public funds investors: it’s extraordinarily hard to call the markets and risky to condition portfolio strategies on calling interest rates.

Rear view mirror analysis suggests good reasons to expect lower short-term rates in coming months. That’s what interest rate futures contracts now indicate, but they’ve had this bias time and again since the Fed last eased rates in December, only to back off in the face of other indications that the economy was sustaining forward momentum. This time the change in yields on one and two year Treasuries also signals the Fed will soon ease as they closed Friday down about one-quarter percent.

While the revised jobs report was a negative for the economy, Trump and his economic team point to other data that they say shows economic expansion. Notably they have made much of tariff deals that they say will lead to hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars of investments in the U.S. economy, but there are several caveats.

One is that the deals are at this point informal; agreements and documentation usually take months or years to complete and the details may or may not match the recent headlines.

The second is that these investments, if they materialize, will be in the future. Meanwhile the main driver of U.S. growth, which is consumption, has weakened measurably in recent quarters. Consumption accounts for about 70% of output so it cannot be overlooked. (Let’s set aside the Through the Looking Glass argument that these statistics too are flawed and that we cannot rely on any mainstream measure of the economy or markets.)

The recent trend of consumer spending, as documented by the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, is worrisome. In the last quarter it grew by 0.6% over the level 12 months earlier. This compares with growth rates of 2%-2. 5% in 2024.

Investment, which is where tariff-related investments are recorded, accounts for about 20% of GDP, so it would take a huge move in investments to offset the pullback by consumers. Crucially investment in the second quarter was a negative for GDP growth.

Investors in the short-end of the market may have ben caught flat-footed by the market move. Money fund and LGIP managers began last week with portfolios positioned for no FOMC move at its July meeting. As the PFII Dashhoard documents, weighted average maturities were in the in the thirty day range. The Cranedata information on money funds confirms this. It showed money fund WAMs of 40 days and the end of last week, vs. 38 days at the beginning of July.

Modest WAMs was for then, but now, with heightened chances that the Fed will lower rates in September by 25 basis points, these managers will be reconsidering their positions. And they will be doing so in an market where short term rates beyond September are lower by 25 basis points.

This week has been one of reassessment. A number of FOMC members have hinted in speeches that a rate cut in September is in the cards. Levels on short-term Treasuries suggest that money market rates a year from now will be closer to three percent than four percent.

Descent into a recession could push rates much lower. So would a monetary policy that adopts Trump’s apparent view that the central bank should reward a successful economy by setting rates at one percent or less. Neither of these is impossible, although the outlook for recession seems to be in the 15%-20% range, even after incorporating the jobs report and other negative data, and Trump’s call for one percent rates would challenge the basics of monetary economics.

What Now?

There are always multiple paths for the economy to follow. For public funds investors whose goal should be to provide resources for their government’s business and avoid ugly surprises the question following Frida’s events should not be which way rates are going next but will constituents be satisfied with results under a variety of out comes?