Why Do Investors Discount Credit Risk?

The markets are awash in headlines about economic uncertainty and the rising prospect of recession, but these forces have barely moved measures of credit risk.

The markets are awash in headlines about economic uncertainty and the rising prospect of recession, but these forces have barely moved measures of credit risk.

Credit backed instruments are a significant part of public funds portfolios. The Federal Reserve estimates that state and local governments held $561 billion of commercial paper and corporate bonds at the end of last year. That’s about 15% of overall investment assets. The holdings are concentrated in prime LGIPs and large separate portfolios where they may make up to 90% of holdings. For these investors performance of credit-backed instruments is the key to overall portfolio results.

History tells us that when the economy weakens and uncertainty rises investors demand a higher premium to invest in corporate commercial paper and bonds. Yet this time around that has not been the case.

Let’s start with the state of the credit markets. In a few words, they represent business as usual.

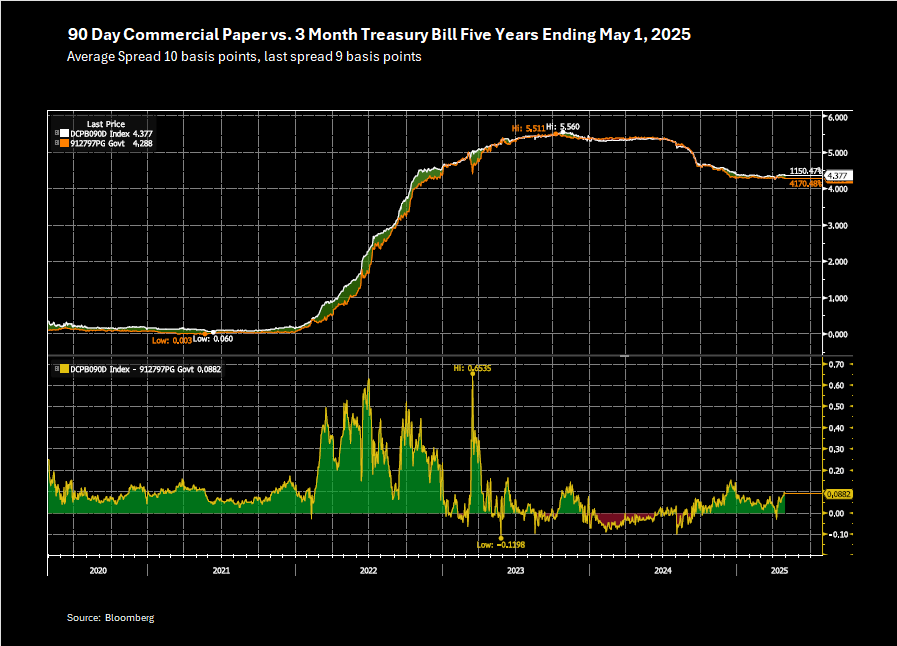

- Commercial paper rates are tracking closely to rates on comparable-maturity Treasuries. The chart below shows the history over the past five years. On average three-month commercial paper has yielded about 10 basis points more than comparable-maturity Treasuries. At this writing, the difference is nine basis points.

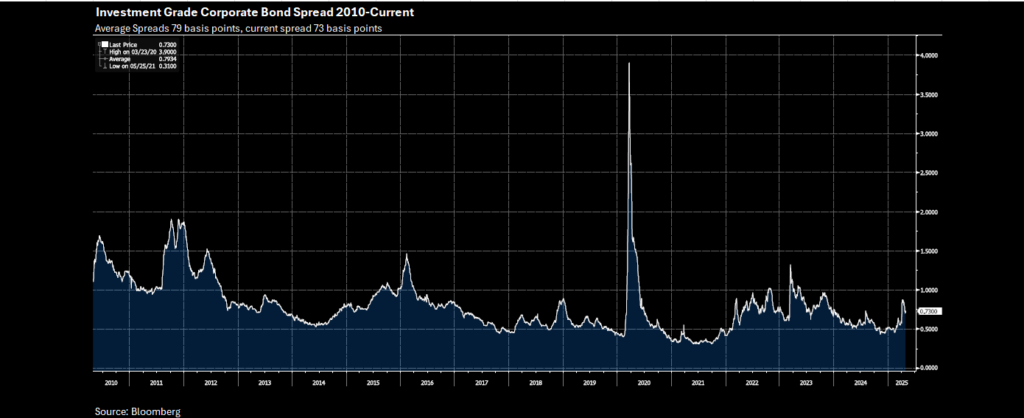

- Corporate bond spreads reflect a similar “what me worry?” view. If you look back at the spreads over the past 15 years, beginning in 2010 when the economy had recovered from the Great Recession, they have averaged 82 basis points. They are now 71 basis points.

- By the way, the same is true for high yield corporate bond spreads. Not that public sector investors hold high yield corporate debt, but many analysts consider this sector to be the first to signal problems for credit.

So, what’s up here? Why haven’t credit spreads gapped wider in recent weeks? There are three possibilities:

The threat of an economic downturn is overblown. In recent weeks there has been a broad move among financial economists to downgrade the prospects for growth and raise the forecast for inflation in the U.S.

At the same time many economists have raised their estimates of the probability of recession. The Bloomberg probability of recession outlook that tracks the consensus of economists is now at 40%, up from 20% in February.

And some well-known economic forecasters have put the likelihood at 50% or higher. Meanwhile the outlook for GDP growth tracked by Bloomberg has been downgraded to 1.4% this year from earlier forecasts of 1.8-2.0%.

Finally, the International Monetary Fund last week lowered its growth forecast to 1.8%, down nearly 1% from January.

These are all forward-looking “guesses”—some well-grounded in research, others perhaps educated (or not?). They could be wrong. Look no further than the spring of 2023 when the Bloomberg probability consensus was a 65% chance of recession. But GDP expanded by 2.9% in 2023 and 2.8% last year.

Perhaps the credit markets signal is right, and the forecasters are wrong. Could credit market conditions be accurate in their implication that the economy will avoid a downtown and in fact strengthen later in the year?

Issuers of credit are well insulated from the effects of a downturn. A second possibility is that corporate credit is well protected against an economic downturn. Corporations, particularly large financial institutions whose issuance volumes dominate the commercial paper and investment grade corporate markets, have had several years of solid growth in cash flows/profits.

Although the growth has been outrun by stock market expansion (earnings multiples are up), the underlying expansion of cash flows has led the rating agencies to upgrade more credits than they downgraded in the post pandemic period. This favorable upgrade to downgrade ratio continued through the first quarter of 2025

In one key sector, the mega banks have accumulated capital buffers in recent years in anticipation of more stringent capital requirements—requirements that are now not likely to be implemented by the Trump administration. This may not be favorable to bond holders in the long run, but meanwhile the excess capital presents a downside cushion.

Moreover, if the economy turns down but avoids a deep recession interest rates could fall, reducing the cost of borrowing (for debt refinancing) for companies.

There are some contrary indicators, including rising consumer loan and credit card delinquencies. And S&P reported that US corporate bankruptcies reached a 14 year high in 2024, up more than 85% from the level it tracked in 2022.

There is a lot of data to support either view: one, that credit is well-insulated and another that the cushion is fraying. The best thing to say might be that the jury is out on this possibility as well.

Credit markets have not priced in real economic risks. Modest spreads offered by commercial paper and short-term corporate bonds may represent mispricing of risk for these assets. In this case expect credit spreads to widen, maybe by 25-50 basis points over coming months.

If you are a cautious investor you should think about the implications of this mispricing.

Wider spreads in the commercial paper market would represent an investment opportunity but parking money temporarily in anticipation of spread widening has a real cost. For example, you might pass up investing in 90-day commercial paper at a yield of 10 basis points over Treasuries.

Back of an envelope benefit: If the spread were to widen from 10 to 20 basis points after 45 days and you then bought the commercial paper the total of 45 days earning at the lower risk-free rate and 45 days at the higher commercial paper rate would produce the same total earnings over 90 days as if you’d invested on day one in commercial paper. So, you would need spreads to widen by more than 20 basis points to do better than break even.

To note what should be obvious: the problem with this bet is time. Ninety days does not provide a very long runway.

At the other end of the maturity spectrum, one could consider a five-year corporate note. Today it might have a yield of around 5%, earning $250,000 over five years on a $1 million investment. If spreads were to widen by say 25 basis points after 90 days, that might add about $12,000 to overall earnings for the period.

But also important is that if you purchased the corporate note today at a 5% yield and spreads widened by the same 25 basis points after 90 days, the widened spread would create an unrealized market value loss of around 1%. This would be reported someplace on your financial statement.

The markets may be efficient, but that’s not the same as saying that markets do not misprice from time to time. The credit markets today may represent just such a mispricing.

Bottom line.

Now is not a great time to invest in corporate credit. Spreads have been stable—a welcome condition in the face of market turmoil–but they are at historically narrow levels, with the result that commercial paper and short-term corporate bonds have made a limited contribution to first quarter portfolio returns. They could perform well if the economy avoids a recession, but if not, expect a bumpy road ahead.