A Big Week for the Bond Market

It is a big week for the bond market with a slew of economic releases (jobs, consumer confidence and a few inflation measures), the Federal Open Market Committee meeting (Tuesday/Wednesday) and investors desperately seeking direction.

Public sector investors have a constrained universe: they do not generally invest in equities (though a few do), and their maturity boundaries stop at two or three years. In this universe one boundary has hardly moved. The PFII Government LGIP yield index last week was 5.27%; the prime yield index was 5.45%. These are close to where they were at the beginning of the year. The other boundary has moved by nearly 200 basis points (!) since October when two-year Treasury rates peaked at 5.20%, before dropping to a low of 4.15% in January and recovering to about 5% currently.

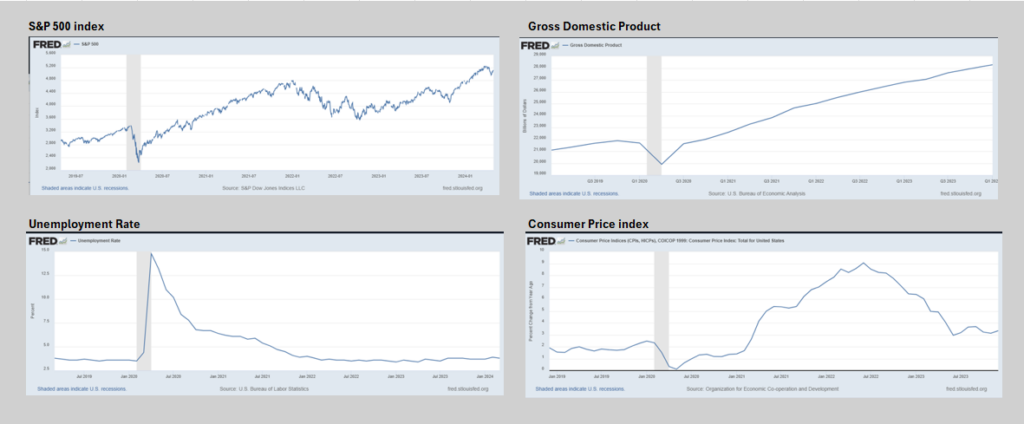

The market activity since January has been notable mostly because there has been a significant move in rates with so little change in current economic conditions.

The economy is expanding at a moderate pace, inflation is significantly lower than it was at its peak in the summer of 2022 (but still above the low levels of the pre-pandemic years), stock prices have risen at a surprising pace, and the unemployment rate is low.

Inflation is the focus. The majority of market economists are adamant about promoting a 2% target. They argue that anything higher will lead to misallocation of capital and erode consumer incomes. And the Fed has endorsed this view: returning the economy to a 2% inflation level is central to its policy. (Never mind, as Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winning economist has observed in his just-published book, The Road To Freedom, and in a round of appearances on financial news outlets that there is scant empirical analysis to support this target.)

There is a case to be made that the economy will all come crashing down and we will sink into recession. That would lead the Fed to ease monetary policy sharply. There is also a case to be made that the current economic conditions will persist, and the Fed will make only modest adjustments in its policies. (There is also a minority case that inflation will accelerate and lead to the Fed tightening policy.) Not to say that the business cycle theory of economic activity is dead, just that the length of cycles is unknown.

That all may make interesting reading or conversation but is not very helpful to public funds investors whose options today are similar to the options they faced in early November when two-year Treasuries were last above 5%.

LGIPs or short-term money market investments have earned at over 5%–the highest in a generation. The PFII Prime Index has averaged 5.50% and the Government Index has averaged 5.30% since mid-October. (Keep in mind that LGIPs pay interest monthly; the effect of compounding adds about ten basis points to these yields over a year.) Funds are liquid—a useful attribute in the face of budgetary uncertainty. But earnings persistence can be an issue. If/when the Fed begins to cut, LGIP rates will decline step by step within 30-60 days of each Fed action and the 5% yields now available on two-year Treasuries will also plumet as investors anticipate lower rates ahead. (No, it is not likely you will be able to invest in a two-year Treasury at anywhere close to 5% once the word is out.)

The results of having invested in two-year Treasuries—or the equivalent—in this period should also be satisfying. While this investment does not offer “dollar-in/dollar out” liquidity, an earnings rate of about 5% over a two-year budget cycle is also the highest in a generation. There could be a “cost” for early redemption—if you want to think about it this way—but it is likely to be quite manageable and might even be a gain. If you need your money after a year the “cost” of selling the Treasury note (i.e., the bid side of the market) would be about 0.33% of par (given a continuation of current interest rates). Of course this varies by the then level of interest rates. If the economy has sunk into recession and the Fed has eased rates by say 2%, the “cost” would actually be a gain of about 1.8%. If inflation accelerates and the Fed raises rates by say 1%, the “cost would be about 1.3%.

Seems like a decent deal either way.